Identifying domain-model boundaries for each microservice

The goal when identifying model boundaries and size for each microservice is not to get to the most granular separation possible, although you should tend toward small microservices if possible. Instead, your goal should be to get to the most meaningful separation guided by your domain knowledge. The emphasis is not on the size, but instead on business capabilities. In addition, if there is clear cohesion needed for a certain area of the application based on a high number of dependencies, that indicates the need for a single microservice, too. Cohesion is a way to identify how to break apart or group together microservices. Ultimately, while you gain more knowledge about the domain, you should adapt the size of your microservice, iteratively. Finding the right size is not a one-shot process.

Sam Newman, a recognized promoter of microservices and author of the book Building Microservices, highlights that you should design your microservices based on the Bounded Context (BC) pattern (part of domain-driven design), as introduced earlier. Sometimes, a BC could be composed of several physical services, but not vice versa.

A domain model with specific domain entities applies within a concrete BC or microservice. A BC delimits the applicability of a domain model and gives developer team members a clear and shared understanding of what must be cohesive and what can be developed independently. These are the same goals for microservices.

Another tool that informs your design choice is Conway’s law, which states that an application will reflect the social boundaries of the organization that produced it. But sometimes the opposite is true—the company’s organization is formed by the software. You might need to reverse Conway’s law and build the boundaries the way you want the company to be organized, leaning toward business process consulting.

In order to identify bounded contexts, a DDD pattern that can be used for this is the Context Mapping pattern. With Context Mapping, you identify the various contexts in the application and their boundaries. It is common to have a different context and boundary for each small subsystem, for instance. The Context Map is a way to define and make explicit those boundaries between domains. A BC is autonomous and includes the details of a single domain—details like the domain entities—and defines integration contracts with other BCs. This is similar to the definition of a microservice: it is autonomous, it implements certain domain capability, and it must provide interfaces. This is why Context Mapping and the Bounded Context pattern are good approaches for identifying the domain model boundaries of your microservices.

When designing a large application, you will see how its domain model can be fragmented — a domain expert from the catalog domain will name entities differently in the catalog and inventory domains than a shipping domain expert, for instance. Or the user domain entity might be different in size and number of attributes when dealing with a CRM expert who wants to store every detail about the customer than for an ordering domain expert who just needs partial data about the customer. It is very hard to disambiguate all domain terms across all the domains related to a large application. But the most important thing is that you should not try to unify the terms; instead, accept the differences and richness provided by each domain. If you try to have a unified database for the whole application, attempts at a unified vocabulary will be awkward and will not sound right to any of the multiple domain experts. Therefore, BCs (implemented as microservices) will help you to clarify where you can use certain domain terms and where you will need to split the system and create additional BCs with different domains.

You will know that you got the right boundaries and sizes of each BC and domain model if you have few strong relationships between domain models, and you do not usually need to merge information from multiple domain models when performing typical application operations.

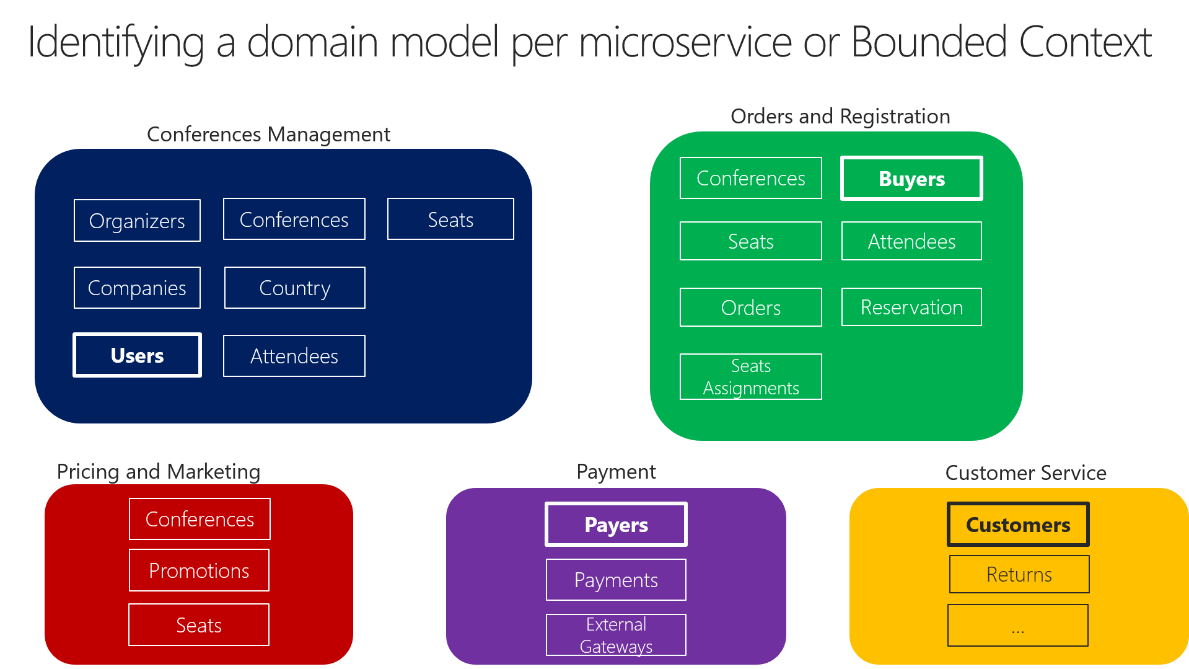

Perhaps the best answer to the question of how big a domain model for each microservice should be is the following: it should have an autonomous BC, as isolated as possible, that enables you to work without having to constantly switch to other contexts (other microservice’s models). In Figure 4-10 you can see how multiple microservices (multiple BCs) each have their own model and how their entities can be defined, depending on the specific requirements for each of the identified domains in your application.

Figure 4-10. Identifying entities and microservice model boundaries

Figure 4-10 illustrates a sample scenario related to an online conference management system. You have identified several BCs that could be implemented as microservices, based on domains that domain experts defined for you. As you can see, there are entities that are present just in a single microservice model, like Payments in the Payment microservice. Those will be easy to implement.

However, you might also have entities that have a different shape but share the same identity across the multiple domain models from the multiple microservices. For example, the User entity is identified in the Conferences Management microservice. That same user, with the same identity, is the one named Buyers in the Ordering microservice, or the one named Payer in the Payment microservice, and even the one named Customer in the Customer Service microservice. This is because, depending on the ubiquitous language that each domain expert is using, a user might have a different perspective even with different attributes. The user entity in the microservice model named Conferences Management might have most of its personal data attributes. However, that same user in the shape of Payer in the microservice Payment or in the shape of Customer in the microservice Customer Service might not need the same list of attributes.

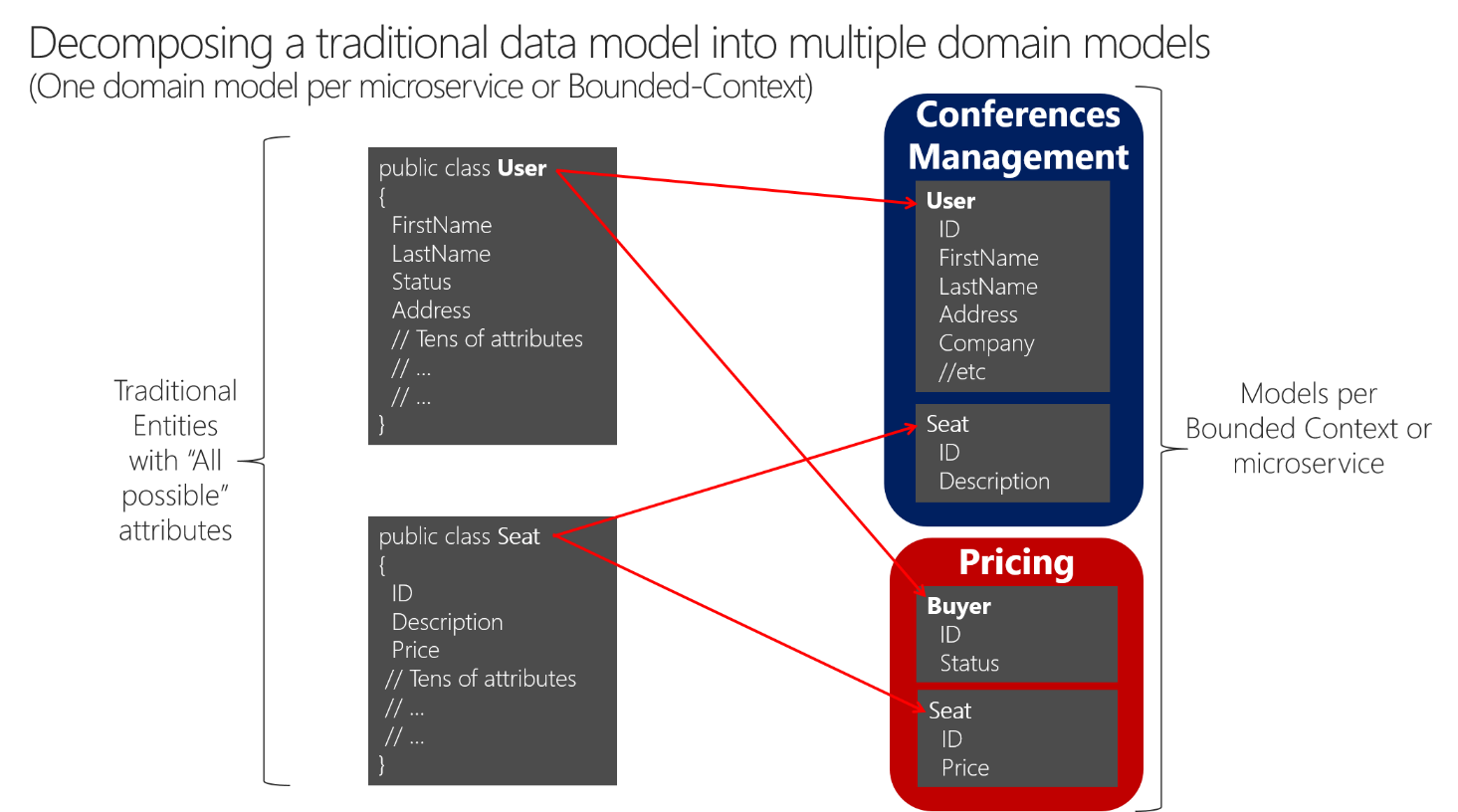

A similar approach is illustrated in Figure 4-11.

Figure 4-11. Decomposing traditional data models into multiple domain models

You can see how the user is present in the Conferences Management microservice model as the User entity and is also present in the form of the Buyer entity in the Pricing microservice, with alternate attributes or details about the user when it is actually a buyer. Each microservice or BC might not need all the data related to a User entity, just part of it, depending on the problem to solve or the context. For instance, in the Pricing microservice model, you do not need the address or the ID of the user, just ID (as identity) and Status, which will have an impact on discounts when pricing the seats per buyer.

The Seat entity has the same name but different attributes in each domain model. However, Seat shares identity based on the same ID, as happens with User and Buyer.

Basically, there is a shared concept of a user that exists in multiple services (domains), which all share the identity of that user. But in each domain model there might be additional or different details about the user entity. Therefore, there needs to be a way to map a user entity from one domain (microservice) to another.

There are several benefits to not sharing the same user entity with the same number of attributes across domains. One benefit is to reduce duplication, so that microservice models do not have any data that they do not need. Another benefit is having a master microservice that owns a certain type of data per entity so that updates and queries for that type of data are driven only by that microservice.

Direct client-to-microservice communication versus the API Gateway pattern

In a microservices architecture, each microservice exposes a set of (typically) fine‑grained endpoints. This fact can impact the client‑to‑microservice communication, as explained in this section.

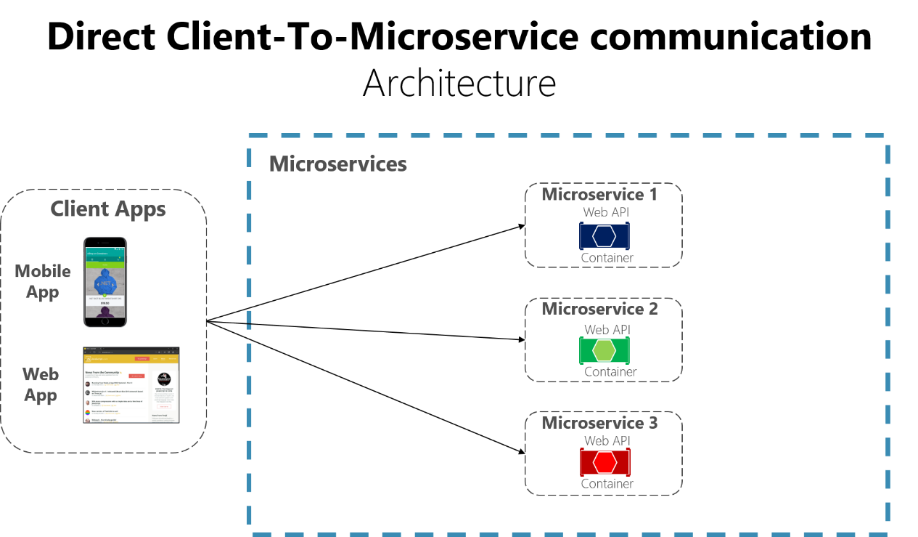

Direct client-to-microservice communication

A possible approach is to use a direct client-to-microservice communication architecture. In this approach, a client app can make requests directly to some of the microservices, as shown in Figure 4-12.

Figure 4-12. Using a direct client-to-microservice communication architecture

In this approach. each microservice has a public endpoint, sometimes with a different TCP port for each microservice. An example of an URL for a particular service could be the following URL in Azure:

http://eshoponcontainers.westus.cloudapp.azure.com:88/

In a production environment based on a cluster, that URL would map to the load balancer used in the cluster, which in turn distributes the requests across the microservices. In production environments, you could have an Application Delivery Controller (ADC) like Azure Application Gateway between your microservices and the Internet. This acts as a transparent tier that not only performs load balancing, but secures your services by offering SSL termination. This improves the load of your hosts by offloading CPU-intensive SSL termination and other routing duties to the Azure Application Gateway. In any case, a load balancer and ADC are transparent from a logical application architecture point of view.

A direct client-to-microservice communication architecture is good enough for a small microservice-based application. However, when you build large and complex microservice-based applications (for example, when handling dozens of microservice types), that approach faces possible issues. You need to consider the following questions when developing a large application based on microservices:

- How can client apps minimize the number of requests to the backend and reduce chatty communication to multiple microservices?

Interacting with multiple microservices to build a single UI screen increases the number of roundtrips across the Internet. This increases latency and complexity on the UI side. Ideally, responses should be efficiently aggregated in the server side—this reduces latency, since multiple pieces of data come back in parallel and some UI can show data as soon as it is ready.

- How can you handle cross-cutting concerns such as authorization, data transformations, and dynamic request dispatching?

Implementing security and cross-cutting concerns like security and authorization on every microservice can require significant development effort. A possible approach is to have those services within the Docker host or internal cluster, in order to restrict direct access to them from the outside, and to implement those cross-cutting concerns in a centralized place, like an API Gateway.

- How can client apps communicate with services that use non-Internet-friendly protocols?

Protocols used on the server side (like AMQP or binary protocols) are usually not supported in client apps. Therefore, requests must be performed through protocols like HTTP/HTTPS and translated to the other protocols afterwards. A man-in-the-middle approach can help in this situation.

- How can you shape a façade especially made for mobile apps?

The API of multiple microservices might not be well designed for the needs of different client applications. For instance, the needs of a mobile app might be different than the needs of a web app. For mobile apps, you might need to optimize even further so that data responses can be more efficient. You might do this by aggregating data from multiple microservices and returning a single set of data, and sometimes eliminating any data in the response that is not needed by the mobile app. And, of course, you might compress that data. Again, a façade or API in between the mobile app and the microservices can be convenient for this scenario.

Using an API Gateway

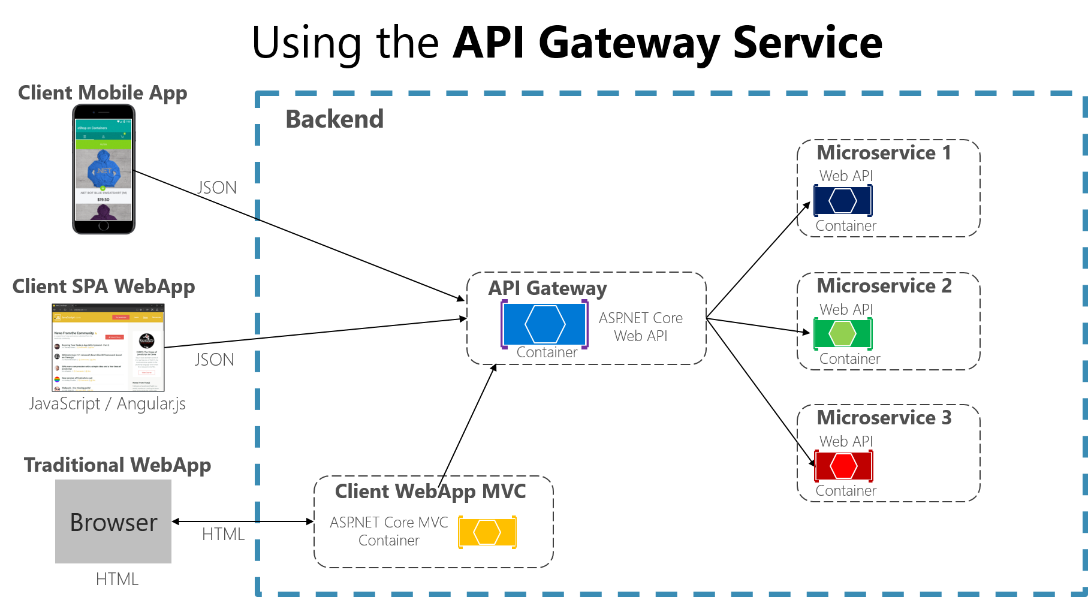

When you design and build large or complex microservice-based applications with multiple client apps, a good approach to consider can be an API Gateway. This is a service that provides a single entry point for certain groups of microservices. It is similar to the Facade pattern from object‑oriented design, but in this case, it is part of a distributed system. The API Gateway pattern is also sometimes known as the “back end for the front end,” because you build it while thinking about the needs of the client app.

Figure 4-13 shows how an API Gateway can fit into a microservice-based architecture.

Figure 4-13. Using the API Gateway pattern in a microservice-based architecture

In this example, the API Gateway would be implemented as a custom Web API service running as a container.

You should implement several API Gateways so that you can have a different façade for the needs of each client app. Each API Gateway can provide a different API tailored for each client app, possibly even based on the client form factor or device by implementing specific adapter code which underneath calls multiple internal microservices.

Since the API Gateway is actually an aggregator, you need to be careful with it. Usually it is not a good idea to have a single API Gateway aggregating all the internal microservices of your application. If it does, it acts as a monolithic aggregator or orchestrator and violates microservice autonomy by coupling all the microservices. Therefore, the API Gateways should be segregated based on business boundaries and not act as an aggregator for the whole application.

Sometimes a granular API Gateway can also be a microservice by itself, and even have a domain or business name and related data. Having the API Gateway’s boundaries dictated by the business or domain will help you to get a better design.

Granularity in the API Gateway tier can be especially useful for more advanced composite UI applications based on microservices, because the concept of a fine-grained API Gateway is similar to an UI composition service. We discuss this later in the Creating composite UI based on microservices.

Therefore, for many medium- and large-size applications, using a custom-built API Gateway is usually a good approach, but not as a single monolithic aggregator or unique central API Gateway.

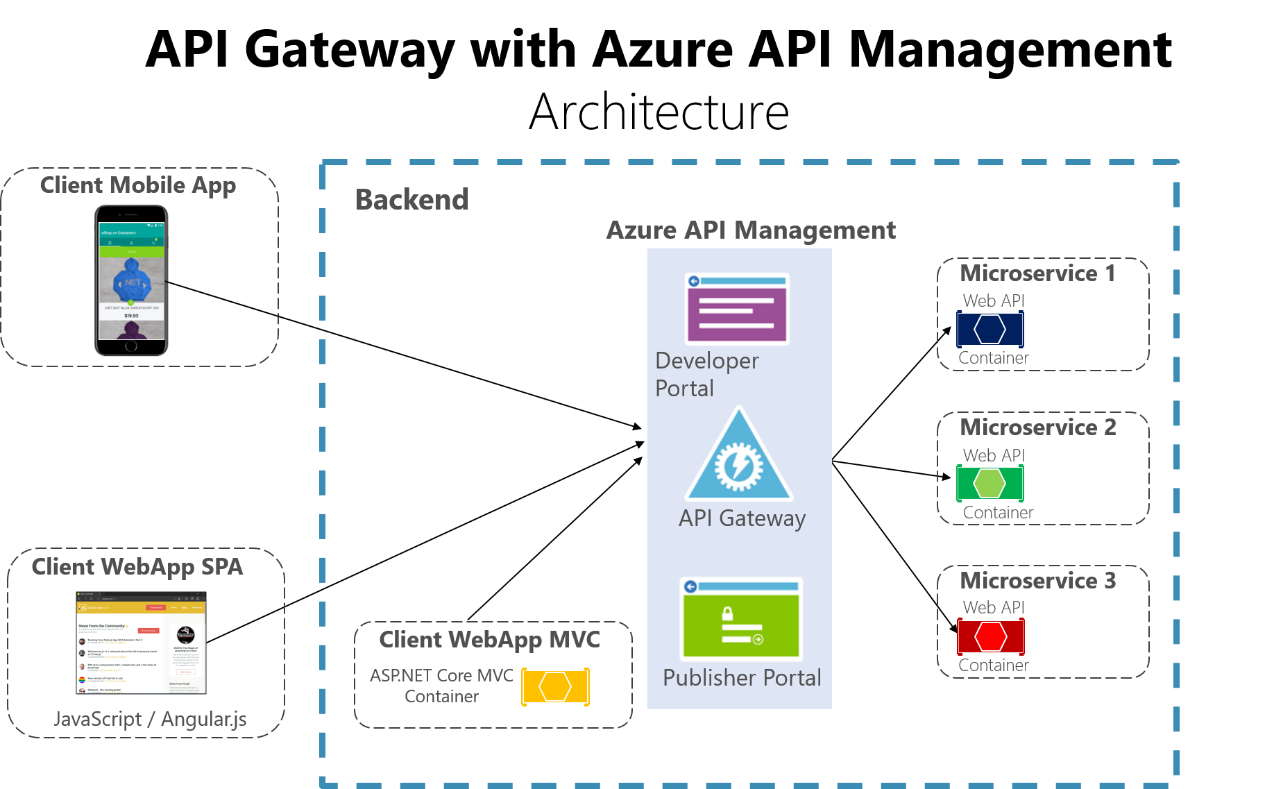

Another approach is to use a product like Azure API Management as shown in Figure 4-14. This approach not only solves your API Gateway needs, but provides features like gathering insights from your APIs. If you are using an API management solution, an API Gateway is only a component within that full API management solution.

Figure 4-14. Using Azure API Management for your API Gateway

The insights available from an API Management system help you get an understanding of how your APIs are being used and how they are performing. They do this by letting you view near real-time analytics reports and identifying trends that might impact your business. Plus you can have logs about request and response activity for further online and offline analysis.

With Azure API Management, you can secure your APIs using a key, a token, and IP filtering. These features let you enforce flexible and fine-grained quotas and rate limits, modify the shape and behavior of your APIs using policies, and improve performance with response caching.

In this guide and the reference sample application (eShopOnContainers) we are limiting the architecture to a simpler and custom-made containerized architecture in order to focus on plain containers without using PaaS products like Azure API Management. But for large microservice-based applications that are deployed into Microsoft Azure, we encourage you to review and adopt Azure API Management as the base for your API Gateways.

Drawbacks of the API Gateway pattern

The most important drawback is that when you implement an API Gateway, you are coupling that tier with the internal microservices. Coupling like this might introduce serious difficulties for your application. (The cloud architect Clemens Vaster refers to this potential difficulty as “the new ESB” in his "Messaging and Microservices" session from at GOTO 2016.)

Using a microservices API Gateway creates an additional possible point of failure.

An API Gateway can introduce increased response time due to the additional network call. However, this extra call usually has less impact than having a client interface that is too chatty directly calling the internal microservices.

The API Gateway can represent a possible bottleneck if it is not scaled out properly

An API Gateway requires additional development cost and future maintenance if it includes custom logic and data aggregation. Developers must update the API Gateway in order to expose each microservice’s endpoints. Moreover, implementation changes in the internal microservices might cause code changes at the API Gateway level. However, if the API Gateway is just applying security, logging, and versioning (as when using Azure API Management), this additional development cost might not apply.

If the API Gateway is developed by a single team, there can be a development bottleneck. This is another reason why a better approach is to have several fined-grained API Gateways that respond to different client needs. You could also segregate the API Gateway internally into multiple areas or layers that are owned by the different teams working on the internal microservices.

Additional resources

Charles Richardson. Pattern: API Gateway / Backend for Front-End http://microservices.io/patterns/apigateway.html

Azure API Management https://azure.microsoft.com/services/api-management/

Udi Dahan. Service Oriented Composition\ http://udidahan.com/2014/07/30/service-oriented-composition-with-video/

Clemens Vasters. Messaging and Microservices at GOTO 2016 (video) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXi5CLjIQ9k

[!div class="step-by-step"] [Previous] (distributed-data-management.md) [Next] (communication-between-microservices.md)