Designing the infrastructure persistence layer

Data persistence components provide access to the data hosted within the boundaries of a microservice (that is, a microservice’s database). They contain the actual implementation of components such as repositories and Unit of Work classes, like custom EF DBContexts.

The Repository pattern

Repositories are classes or components that encapsulate the logic required to access data sources. They centralize common data access functionality, providing better maintainability and decoupling the infrastructure or technology used to access databases from the domain model layer. If you use an ORM like Entity Framework, the code that must be implemented is simplified, thanks to LINQ and strong typing. This lets you focus on the data persistence logic rather than on data access plumbing.

The Repository pattern is a well-documented way of working with a data source. In the book Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Martin Fowler describes a repository as follows:

A repository performs the tasks of an intermediary between the domain model layers and data mapping, acting in a similar way to a set of domain objects in memory. Client objects declaratively build queries and send them to the repositories for answers. Conceptually, a repository encapsulates a set of objects stored in the database and operations that can be performed on them, providing a way that is closer to the persistence layer. Repositories, also, support the purpose of separating, clearly and in one direction, the dependency between the work domain and the data allocation or mapping.

Define one repository per aggregate

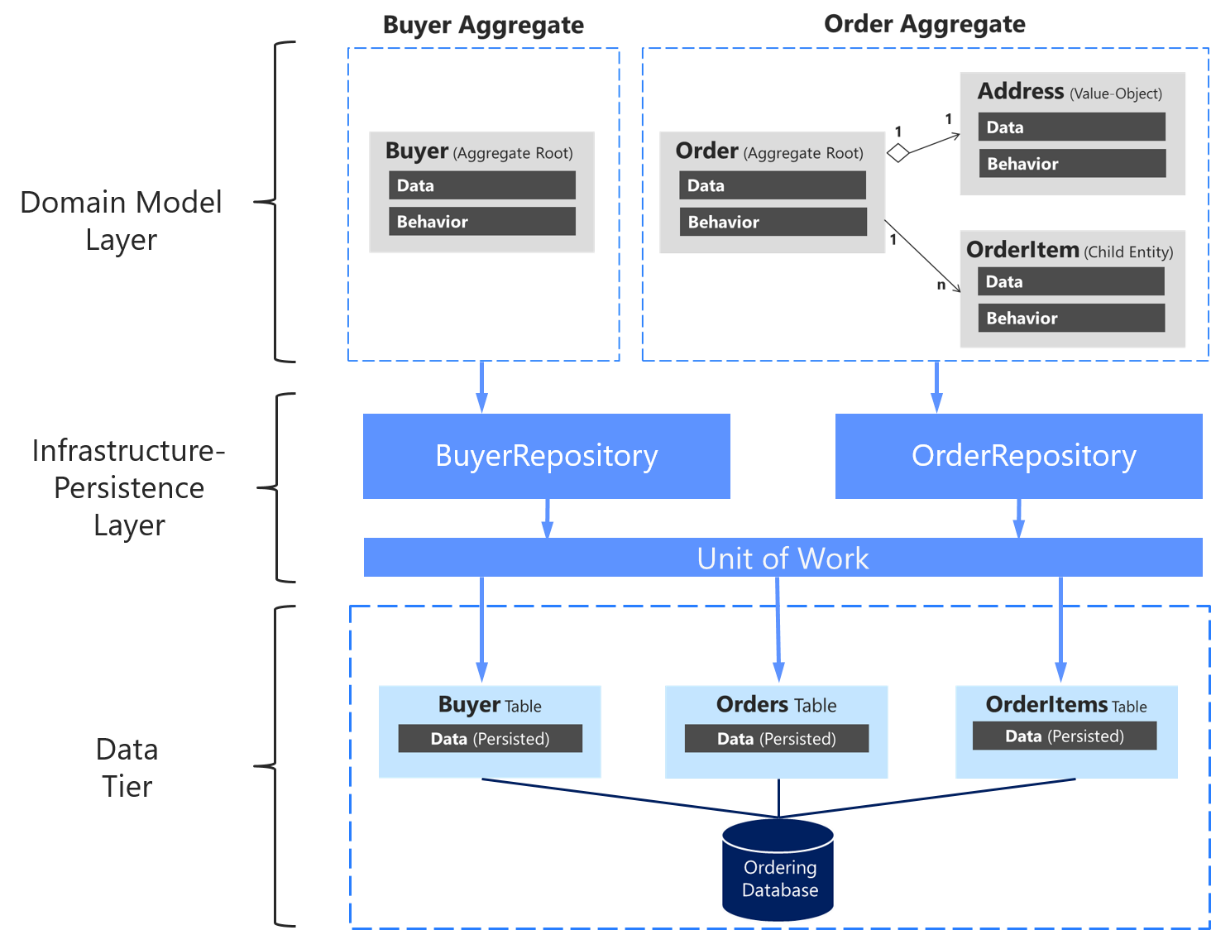

For each aggregate or aggregate root, you should create one repository class. In a microservice based on domain-driven design patterns, the only channel you should use to update the database should be the repositories. This is because they have a one-to-one relationship with the aggregate root, which controls the aggregate’s invariants and transactional consistency. It is okay to query the database through other channels (as you can do following a CQRS approach), because queries do not change the state of the database. However, the transactional area—the updates—must always be controlled by the repositories and the aggregate roots.

Basically, a repository allows you to populate data in memory that comes from the database in the form of the domain entities. Once the entities are in memory, they can be changed and then persisted back to the database through transactions.

As noted earlier, if you are using the CQS/CQRS architectural pattern, the initial queries will be performed by side queries out of the domain model, performed by simple SQL statements using Dapper. This approach is much more flexible than repositories because you can query and join any tables you need, and these queries are not restricted by rules from the aggregates. That data will go to the presentation layer or client app.

If the user makes changes, the data to be updated will come from the client app or presentation layer to the application layer (such as a Web API service). When you receive a command (with data) in a command handler, you use repositories to get the data you want to update from the database. You update it in memory with the information passed with the commands, and you then add or update the data (domain entities) in the database through a transaction.

We must emphasize again that only one repository should be defined for each aggregate root, as shown in Figure 9-17. To achieve the goal of the aggregate root to maintain transactional consistency between all the objects within the aggregate, you should never create a repository for each table in the database.

Figure 9-17. The relationship between repositories, aggregates, and database tables

Enforcing one aggregate root per repository

It can be valuable to implement your repository design in such a way that it enforces the rule that only aggregate roots should have repositories. You can create a generic or base repository type that constrains the type of entities it works with to ensure they have the IAggregateRoot marker interface.

Thus, each repository class implemented at the infrastructure layer implements its own contract or interface, as shown in the following code:

namespace Microsoft.eShopOnContainers.Services.Ordering.Infrastructure.Repositories

{

public class OrderRepository : IOrderRepository

{

Each specific repository interface implements the generic IRepository interface:

public interface IOrderRepository : IRepository<Order>

{

Order Add(Order order);

// ...

}

However, a better way to have the code enforce the convention that each repository should be related to a single aggregate would be to implement a generic repository type so it is explicit that you are using a repository to target a specific aggregate. That can be easily done by implementing that generic in the IRepository base interface, as in the following code:

public interface IRepository<T> where T : IAggregateRoot

The Repository pattern makes it easier to test your application logic

The Repository pattern allows you to easily test your application with unit tests. Remember that unit tests only test your code, not infrastructure, so the repository abstractions make it easier to achieve that goal.

As noted in an earlier section, it is recommended that you define and place the repository interfaces in the domain model layer so the application layer (for instance, your Web API microservice) does not depend directly on the infrastructure layer where you have implemented the actual repository classes. By doing this and using Dependency Injection in the controllers of your Web API, you can implement mock repositories that return fake data instead of data from the database. That decoupled approach allows you to create and run unit tests that can test just the logic of your application without requiring connectivity to the database.

Connections to databases can fail and, more importantly, running hundreds of tests against a database is bad for two reasons. First, it can take a lot of time because of the large number of tests. Second, the database records might change and impact the results of your tests, so that they might not be consistent. Testing against the database is not a unit tests but an integration test. You should have many unit tests running fast, but fewer integration tests against the databases.

In terms of separation of concerns for unit tests, your logic operates on domain entities in memory. It assumes the repository class has delivered those. Once your logic modifies the domain entities, it assumes the repository class will store them correctly. The important point here is to create unit tests against your domain model and its domain logic. Aggregate roots are the main consistency boundaries in DDD.

The difference between the Repository pattern and the legacy Data Access class (DAL class) pattern

A data access object directly performs data access and persistence operations against storage. A repository marks the data with the operations you want to perform in the memory of a unit of work object (as in EF when using the DbContext), but these updates will not be performed immediately.

A unit of work is referred to as a single transaction that involves multiple insert, update, or delete operations. In simple terms, it means that for a specific user action (for example, registration on a website), all the insert, update, and delete transactions are handled in a single transaction. This is more efficient than handling multiple database transactions in a chattier way.

These multiple persistence operations will be performed later in a single action when your code from the application layer commands it. The decision about applying the in-memory changes to the actual database storage is typically based on the Unit of Work pattern. In EF, the Unit of Work pattern is implemented as the DBContext.

In many cases, this pattern or way of applying operations against the storage can increase application performance and reduce the possibility of inconsistencies. Also, it reduces transaction blocking in the database tables, because all the intended operations are committed as part of one transaction. This is more efficient in comparison to executing many isolated operations against the database. Therefore, the selected ORM will be able to optimize the execution against the database by grouping several update actions within the same transaction, as opposed to many small and separate transaction executions.

Repositories should not be mandatory

Custom repositories are useful for the reasons cited earlier, and that is the approach for the ordering microservice in eShopOnContainers. However, it is not an essential pattern to implement in a DDD design or even in general development in .NET.

For instance, Jimmy Bogard, when providing direct feedback for this guide, said the following:

This’ll probably be my biggest feedback. I’m really not a fan of repositories, mainly because they hide the important details of the underlying persistence mechanism. It’s why I go for MediatR for commands, too. I can use the full power of the persistence layer, and push all that domain behavior into my aggregate roots. I don’t usually want to mock my repositories – I still need to have that integration test with the real thing. Going CQRS meant that we didn’t really have a need for repositories any more.

We find repositories useful, but we acknowledge that they are not critical for your DDD, in the way that the Aggregate pattern and rich domain model are. Therefore, use the Repository pattern or not, as you see fit.

Additional resources

The Repository pattern

Edward Hieatt and Rob Mee. Repository pattern. http://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/repository.html

The Repository pattern https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ff649690.aspx

Repository Pattern: A data persistence abstraction http://deviq.com/repository-pattern/

Eric Evans. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. (Book; includes a discussion of the Repository pattern) https://www.amazon.com/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215/

Unit of Work pattern

- Martin Fowler. Unit of Work pattern. http://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/unitOfWork.html

- Implementing the Repository and Unit of Work Patterns in an ASP.NET MVC Application https://www.asp.net/mvc/overview/older-versions/getting-started-with-ef-5-using-mvc-4/implementing-the-repository-and-unit-of-work-patterns-in-an-asp-net-mvc-application

[!div class="step-by-step"] [Previous] (domain-events-design-implementation.md) [Next] (infrastructure-persistence-layer-implemenation-entity-framework-core.md)